By Chase Weber, SDSU Biology Major with an Engineering Minor, Class of 2026.

Key takeaways

- LLMs create responses based on statistical relevance, not absolute accuracy.

- Quality responses require thoughtful prompting.

- LLM utility depends on collaboration rather than consumption.

Abstract

The evolution of Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools from a novel curiosity to an essential collaborator represents both a profound risk and a significant opportunity. Writing, coding, content development, and many other fields are quickly approaching dependence on these tools in an attempt to maximize efficiency and innovation. However, in order to be optimized, these tools must be incorporated in a safe and responsible way. By implementing safe practices, large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Perplexity, and Grok can be incorporated into workflows in an increasingly useful way. In this article, I explore the history and mechanisms of LLMs, how to avoid hallucinations and practical tips on how to use these tools.

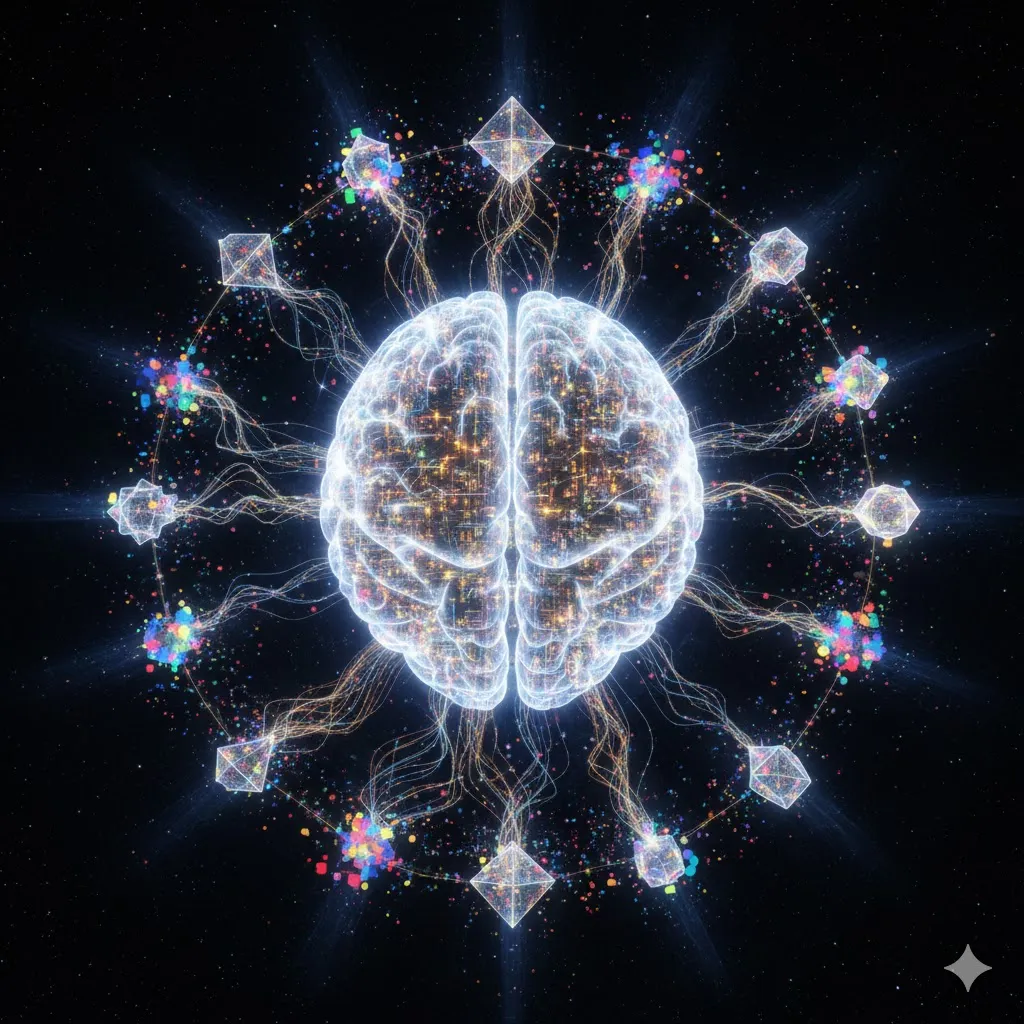

The Genesis of Generative AI: Machine Learning

At its core, generative AI is a machine learning (ML) model, a foundational technology created decades ago. Tools such as text autocomplete, YouTube recommendations, and spam email detection are examples of machine learning. This process enables models to recognize patterns from data, creating the ability to predict future outcomes in the absence of static rules.2

To achieve this, models must undergo an iterative process known as model training. The model begins by producing random outputs, but through errors and feedback, it learns to align with desired results.8 The average difference between model outputs and desired outputs is known as the cost function, and training aims to minimize this. To do so, the model updates its internal parameters: the weights, biases and embeddings.1

Inputs are broken down into tokens, which are units of data such as words, subwords, and image patches. Every token is assigned a fixed numerical ID that corresponds to a specific vector within an embedding matrix. This vector can map the token’s location in geometric space, and these vectors are adjusted during training to converge similar tokens. Simultaneously, layer parameters, which navigate the spatial distances between embeddings via geometric transformations, are adjusted to optimize next token prediction.

What “Meaning” Means

It is important to understand that meaning in this context must be separated from our human perspective of meaning. When we think of the word dog, we can define it using words or ideas. They have paws, 4 legs, big ears, etc. However, the real conceptual meaning of what a dog is can be understood in the absence of words. We have a sensory understanding, emotional attachments, perceptions and memories that ground our understanding of what a dog is. For ML models (with the exception of multimodal models), the word dog simply exists as tokens of text, sitting close to other tokens that relate to it in the embedding matrix. In other words, while these models somewhat understand meaning, it is more accurate to say they understand relationships.

Model Training

In order to proceed from an input to an output, the input moves through a series of layers that each contain parameters known as weights and biases. A layer is like a machine in an assembly line; it receives an input and refines it to create an output that serves as an input for the next layer.1 The input is the original embedding of the tokens, and these change mathematically by the time they pass through all of the layers. The layers together serve as an artificial neural network, containing a sequence of layers that develop more complex conceptual relationships over time.

- Initial layers serve to learn general, low-level features.

- Middle layers serve to combine the initial layers’ features into complex, often abstract concepts.

- Final layers synthesize those concepts into a statistically accurate final meaning.4

The complexity and depth of these layers varies significantly, ranging from shallow networks with very few layers to deep neural networks often containing hundreds. Simpler machine learning model layers implement linear transformations called affine transformations. In an affine transformation, the refinements are weights and biases that mathematically change the input in order to create an output. This can be understood through the equation: y = mx + b

- y is the output

- m is the weight

- x is the input

- b is the bias

The weight is a multiplier, serving to increase or decrease the influence of a given token and alter its relation to other tokens. This results in rotations, scaling, and other vector transformations that change the orientations of token vectors within the embedding space. Rotation allows the model to shift related words in tandem without altering their relative distance to each other. For example, if the words aunt and uncle are rotated together, the vector that connected them (the parental siblings vector) remains unchanged, but their position relative to unrelated vectors, such as vehicles, is shifted.

Scaling specifically impacts the influence by multiplying predictive dimensions of an input by a large scale factor and nonpredictive dimensions of an input by a near zero scale factor. In the sentence “Robert is riding his bike”, the model would learn that “riding” is a greater predictor of the final meaning than the word “is”, so the weight is adjusted to mathematically reflect that difference in predictive ability.

While there are other geometric transformations that can occur with weights, the general goal is to adjust the input in order to match semantic and conceptual similarity with proximity in the embedding space. A bias term also adjusts the vector, but instead of multiplying, it serves as a constant. Mathematically, the bias ensures that for each layer, a non-zero output will be created by translating all of the tokens. It also helps with fitting the model to data more flexibly, making it easier to represent nuanced relationships in the data.

These aspects of an affine transformation capture the basic ways a model learns to create relationships and meaning, but more complicated non-linear transformations allow for new relationships that can more completely represent meaning. These non-linear functions form the foundation of deep learning, a more sophisticated version of machine learning.

From Machine Learning to Deep Learning

Image taken from “A Deeper Understanding of Deep Learning” at www.dataiku.com 3

Generative AI moves a step beyond basic machine learning into deep learning. In traditional machine learning algorithms, models are typically only able to learn with the support of humans. This means data scientists have to manually identify what features a model should look for and use. However, deep learning has the ability to identify important features itself, greatly reducing the time and effort previously required.3 Deep learning’s capacity for automatic learning stems from its depth, nonlinearity and optimization.

- Depth: Where deep learning gets its name. To be categorized as “deep”, these models must contain more than 3 layers. However, deep learning models can contain up to thousands of layers, each solving an individual task. This results in more transformations that are completed, and thus more complexity that can be mathematically represented and understood.

- Nonlinearity: Using only linear transformations, such as affine transformations, results in a stack of linear layers that collapse into a single linear map. Nonlinear transformations completely change the input space, expanding the limits of what relationships are possible.

- Optimization: backpropagation enables efficient calculations of the gradient of the loss function. This gradient provides optimization algorithms like gradient descent the inputs they need to identify what changes need to be made to individual parameters in order to minimize the cost function.

Deep learning underlines the Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) that take a step closer to modern LLMs. These ANNs are modeled after the human brain, and consist of many interconnected neurons that individually perform mathematical operations. The neurons exist in layers, where the operations done in one layer are passed on to the next layer once complete. The sequence begins with the input layer, which receives the raw data. Next is the hidden layers, where the mathematical operations take place. The final step is the output layer, where a final classification or prediction is made. This multi-layered process enables networks to find complex patterns that even human programmers struggle to find. In theory, deep learning neural networks can approximate any function that exists.11 In other words, every possible input anyone could possibly conceive has a corresponding output. While non-deep networks could possibly do this as well, more parameters would be needed, creating a process that would be less efficient. Deep learning facilitates an efficient, comprehensive way to create statistical accuracy.5

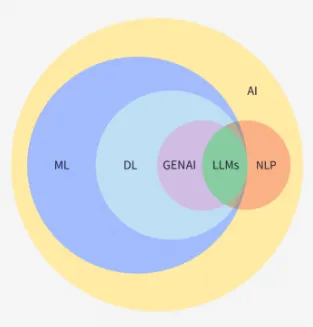

Neural Networks: Sequential Processing, the origin of memory

Prior to LLMs, sequence modeling tasks such as text generation and translation typically relied on Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and variants of RNNs. RNNs are a type of neural network designed to handle sequences by remembering previous inputs via the hidden state, which serves as its memory. Its ability to remember is what separates it from the standard neural network that is unable to recall past inputs. Instead of strictly passing data forward, it cycles information back into the hidden layer to generate a global context.

During training, the model’s output is compared to a desired output, and a loss function measures the difference between them. In order to correct the mistakes, backpropagation through time (BPTT) calculates how each weight impacted the total loss as a gradient (partial derivative of loss with respect to each weight). The weights are then updated using gradient descent, aiming to reduce the loss. The process of gradient descent is analogous to an assignment of blame to individual parameters within the model. While there is only one cost function for a given output, the gradient calculates how much of that cost is due to an individual parameter. Every weight receives its own gradient, and minimizing every single gradient achieves the goal of reducing the total cost. The minimum cost is like the very bottom of the lowest valley in a landscape. Within this landscape there are hills and other valleys, each corresponding to higher and lower total cost values. The gradients point the model towards the direction of steepest increase, so moving in the opposite direction points toward the steepest decrease.1 This corresponds with the direction and magnitude of the weights that are to be adjusted for minimum cost.

Variants of gradient descent such as Stochastic Gradient Descent and Mini-batch Gradient Descent focus on specific aspects such as speed, escaping local minima, and efficiency,9 solving issues that arise from the standard gradient descent model. While variants and optimizers created short term solutions, the main issue could only be solved by a change in structure.

The Limits of Sequential Processing

RNNs began as an important advancement in managing sequential data, but the strategy of processing inputs sequentially led to two key gradient limitations: the vanishing gradient problem and the exploding gradient problem. These gradient problems occur when gradients become too large or too small due to the repeated multiplication design of BPTT. When it reviews its outputs during BPTT, many derivatives are calculated and multiplied together.

- Exploding Gradient Problem

- If the derivatives are slightly larger than 1, multiplying them over and over leads to exponential growth, otherwise known as the exploding gradient problem. This leads the model to become numerically unstable with uncontrollable weight growth and fluctuating loss functions effectively preventing the network from learning anything useful.

- Vanishing Gradient Problem

- When the gradients being multiplied are slightly smaller than 1, this can lead to exponentially small numbers. This leads the model to experience stagnant learning, where the weights in the earlier layers of the network stop updating, effectively causing the training process to stop prior to reaching an optimal solution.

Imagine trying to learn simple math after making a mistake. You guessed one plus one equals three, which is incorrect but has a simple fix. Instead of calmly telling you the answer is two, your teacher starts screaming at you saying your answer is too large. Overwhelmed, you overadjust and guess the answer is negative 100. That is like an exploding gradient problem. The vanishing gradient problem captures the opposite effect. Referring back to the last analogy, instead of screaming at you, the teacher is now whispering so quietly that you can’t hear them. Instead of wildly overadjusting, you do not change your answer at all despite its inaccuracy.

The sequential bottleneck reveals another limitation in RNNs. The recurrent design means processing tokens one step at a time. This type of processing created numerous challenges for RNNs:

- Prolonged training and output generation times: Sequence processing of BPTT and output generation prolongs these processes, especially for large datasets and large inputs.

- Inefficient energy usage: Serial processing prevents efficient computation distribution among multiple processing units.

- Deteriorating context understanding: as sequences grow, earlier information is weighted less than more recent information creating a bias towards recent hidden states and weakening long-term context understanding.

Solving the Sequential Processing Issues with the Emergence of Transformers and Self-Attention

Made with Google Gemini 3.0

In 2017, Google released the paper “Attention is All You Need”, introducing the transformer architecture that powers Chat-GPT (Generative pre-trained Transformer) and others like it. These transformers discarded the old sequential model of processing data and created a new way to process an entire sequence of tokens simultaneously. The new mechanism allowing this breakthrough was self-attention, which is the first sublayer of an encoder layer in a transformer. In self-attention, every token is evaluated against every other token in order to form attention scores.1 These attention scores represent the level at which one token impacts another token, creating a contextual understanding of an entire sequence regardless of length. In order to calculate the scores, three vectors are involved for every single token:

- Query (Q): What a token is looking for in a key vector. The Query vector is the product of every embedding in a sequence and a learned query matrix creating an array of query vectors.

Ex: The token “cool” might have a query vector that looks for nouns to describe, such as “temperature” or “shirt”.

- Key (K): How a token identifies, looking to “answer” the query. The key vector is the product of every embedding of a sequence and a learned key matrix creating an array of key vectors.

Ex: the token “temperature” identifies as a noun that relates to the query “cool”.

- Value (V): The adjustment that can be applied to a query token’s representation to create a contextual definition that prioritizes the key’s token. The value vector is the product of every embedding of a sequence and a learned value matrix creating an array of values.

Ex: the value associated with the key “temperature” is able to alter where the query token “cool” is in the embedding space. This shift ensures that “cool” is more closely related to temperature-like tokens such as “cold” or “farenheit” than shirt-like tokens such as “fashion” or “swag” within this context. The amount in which it does this is determined by the similarity determined between “cool” and “temperature”.

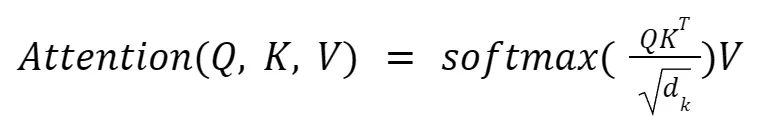

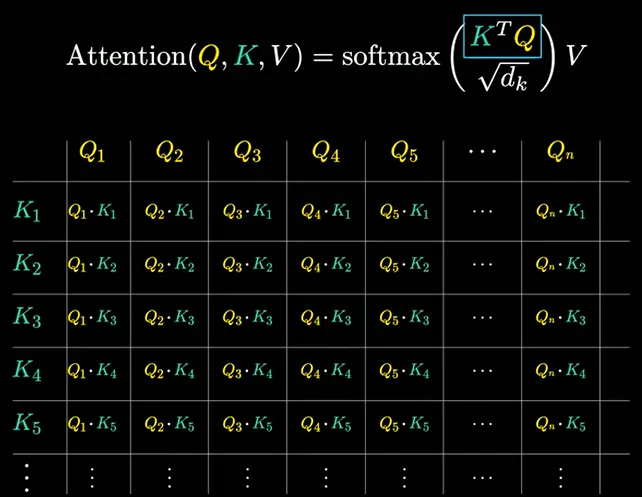

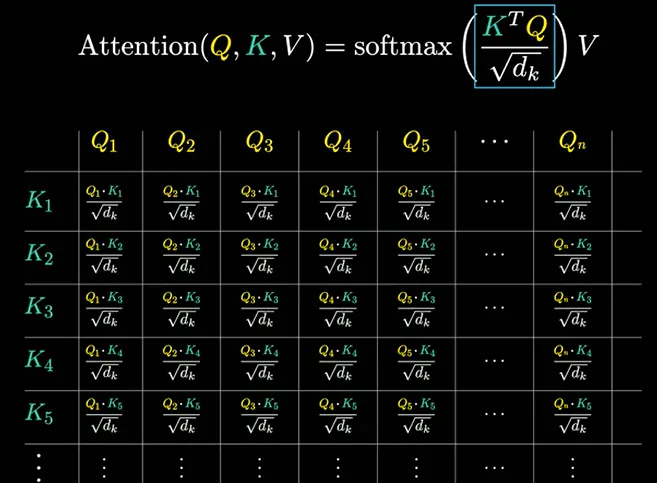

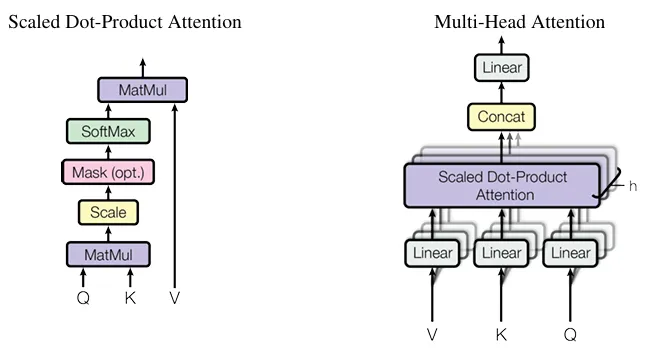

These vectors make up the specific form of attention described by the authors: Scaled Dot Product Attention. Within every attention head, this is the underlying equation that determines the attention score:

- QKT (The Dot Product): The query of every token is multiplied with the key of every token, and the result is a similarity score. If these two vectors are aligned, the product will be a large positive number, meaning a high similarity.

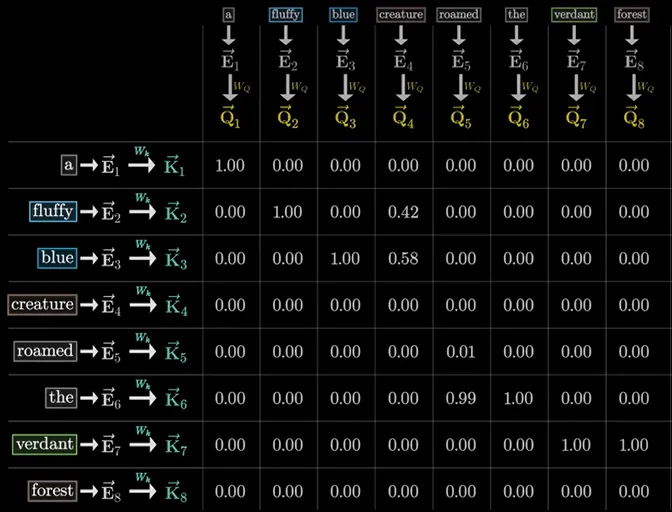

Image from 3Blue1Brown - 1⁄√dk (The Scaling Factor): In high dimensions, dot products can become very large. If these numbers are not reduced, the softmax function would focus only on the greatest number and ignore the rest, creating exploding gradients. The scaling factor reduces these numbers, preventing exploding gradients.

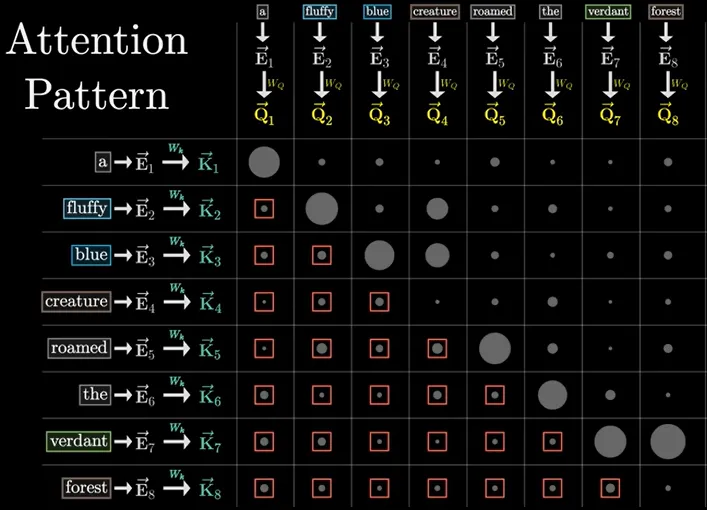

Image from 3Blue1Brown - Softmax (The Probability Normalizer): Scores are converted from numbers to probabilities between 0 and 1. This changes similarity scores into weights that can be compared to others in the same column creating an attention pattern.

Image from 3Blue1Brown using the sequence “a fluffy blue creature roamed the verdant forest” - V: As mentioned earlier, V is the change that can be given to a query representation. Multiplying by V allows a proportion of that change, determined by the rest of the equation, to be implemented in order to better represent the token.

Image from 3Blue1Brown using the sequence “a fluffy blue creature roamed the verdant forest”

- QKT (The Dot Product): The query of every token is multiplied with the key of every token, and the result is a similarity score. If these two vectors are aligned, the product will be a large positive number, meaning a high similarity.

The result of this attention equation is a vector that, when added to the original embedding vector, more accurately represents a token in the context of the sequence it is within. This occurs for every token in the sequence, creating a series of refined meanings throughout. In other words, tokens evolve from isolated definitions into interconnected definitions that create context. However, this is only a single head of attention, which alone would not be enough to completely capture context. Multi-head attention creates an architecture where numerous attention operations occur simultaneously, each with distinct Q, K, and W Matrices. This allows each attention head to pay attention to specific contextual patterns, although what exactly the patterns are is difficult to decipher.10

While the original paper proposed 8 attention heads, LLMs often use more, such as GPT-3 which uses 96 attention heads within each multihead sublayer. These different attention heads run in parallel, and after concatenation (placing resulting vectors side by side) one long vector is formed. This vector is to then be used in the next sublayer of a transformer, the Feed-Forward Network (FFN). Several transformations precede the FFN after the generation of the concatenated vector, including a linear transformation with an output projection, residual connections, and layer normalization. However, for conceptual understanding, the new contextual meaning generated by the attention sublayer can be thought of as being the input into the FFN.

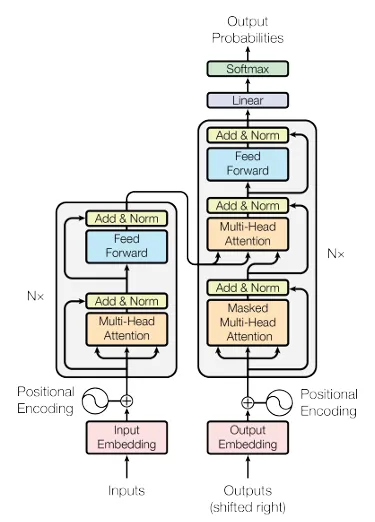

Images from “Attention Is All You Need” by Vaswani et al. 2017

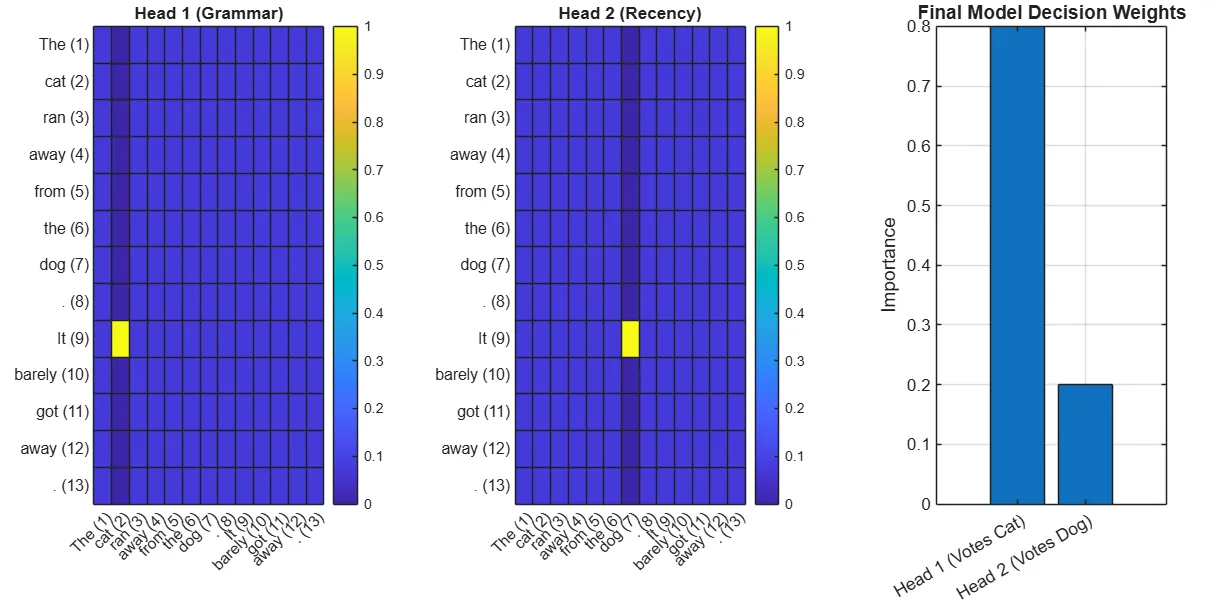

The power of multi-headed attention

Image generated with MATLAB: two simulated attention heads’ heat maps of the sequence “The cat ran away from the dog. It barely got away.”

In this example showing the power of multi-headed attention the models use two simulated attention heads to understand what the sentence means. It’s important to clarify that we don’t actually know what’s happening inside the model, this is simply an illustrative example to build intuition. In this scenario, the final decision layer looks across Head 1 and Head 2 to determine which signal is most relevant. For this example, it weighs the evidence and concludes that cat is the most contextually appropriate choice.

Differing from the Attention sublayer, the Feed-Forward Network acts independently on each token of a sequence. This is where the model stores facts,1 providing additional information that does not depend on context. Each token of the sequence goes through the same equation individually. The equation associated with the FFN is:

- X (The Input): A token’s vector as it enters the FFN sublayer.

- xW1 +b1 (The Expansion): W1 is known as an up-projection, turning a smaller vector into a larger dimension. A learnable bias b1 is also added to the result. In this step, the model is essentially asking many questions, trying to categorize the token.

- max(0,…) (ReLu, The Activation): Negative results from the first step, corresponding to “No” responses become 0, while positive numbers remain. In this step, a filter is applied to the tokens, honing in on what is important and relevant for a given token.

- W2 +b2 (The Compression): W2 is known as a down-projection, taking the filtered, high-dimensional vector, and returning it to its original size prior to expansion. A learnable bias b2 is also added to the result. In this step, the useful information is incorporated into the token.

The final result of this equation is added to the original input vector, producing a new vector. The same transformations that follow the attention results (linear transformation with an output projection, residual connections, and layer normalization) are applied to this vector, completing the journey through a single encoder layer. While the original paper specified both an encoder and decoder layer, almost all LLM’s today use strictly decoder layers. These decoder layers are the key to Generative AI.

Image from “Attention is all you need” by Vaswani et al. 2017

How Generative AI Produces Responses: Decoder Layers

The Decoder layers have essentially the same makeup as the encoder layers: multihead attention, ReLu, normalization, and FFNs, with small details adjusted to account for differences in purpose. The encoder layers serve to process and make sense of an input, while the decoder layers serve to generate outputs. The original Google paper proposed a encoder → decoder sequence, originally for the purpose of translating text. The LLMs of today have abandoned this duality, opting for decoder-only transformers instead.

The self-attention mechanism in decoder layers goes through a process known as masking to prevent current tokens from peeking at newer tokens. So in the sentence “Jack ran up the hill, when the model is looking at the token “the” it only sees tokens to its left. Instead of seeing “hill” in front of “the” the model has to predict what comes next using all of the previous tokens. Prior to softmax in the attention pattern, queries of tokens that attend to keys of tokens in front of it in a sequence, are set to negative infinity. This results in them becoming 0 after softmax, while maintaining the integrity of normalization. In the following image, the dots within the red squares are set to negative infinity.

Image from 3Blue1Brown using the sequence “a fluffy blue creature roamed the verdant forest”

By masking future tokens, the model can learn prediction patterns, as opposed to simply memorizing sequences. Once a decoder has gone through the repetition of layers, a final vector is generated as a context-full embedding. This vector is projected onto the entire token vocabulary, creating a set of raw scores known as logits. To control the freedom of the responses, a temperature value is applied to these logits.

- Scaling: Logits are divided by the temperature

- Softmax: Normalization is applied, turning the logits into a probability distribution

A higher temperature results in a flattening of the distribution, while a lower temperature sharpens the differences within the distribution. Higher temperature creates more creative outputs, while lower temperature creates more deterministic outputs.

The Importance of Understanding Hallucinations

A hallucination occurs when an LLM generates factually incorrect information, invented details, unsupported claims, or content that doesn’t correspond to real-world data even though the output looks polished, plausible, and authoritative.6

LLMs are designed to respond via probabilistic prediction and pattern recognition, but do not have a true understanding of everything. They write to continue text that looks similar to what it has seen before in training. Maximize P(next token | previous tokens). No such thing as maximize P(next token | truth)

This is why people sometimes call it a “super-smart autocomplete”. These models are made to create confident answers, which makes it harder to know when they are wrong.7

The best way to prevent hallucinations is to understand why they happen. Here are some common reasons.

Reasons Why Hallucinations Happen

Missing or incomplete training context

LLMs depend on their training data to generate responses. When faced with a prompt requiring knowledge they don’t possess, they rely on probability rather than fact, often producing plausible-sounding but inaccurate information.

Signal to noise ratios

Certain token relationships can become statistically stronger than they should be due to training data biases or architecture. Things can be highly correlated without being causally related.

Context drift

Since each new prediction depends on both the input and previous predictions, even small biases or fallacies can lead to greater inaccuracies over a whole response.

When Hallucinations are Most Likely

- Highly specific or hard to find information

- Highly vague or unclear direction

- Answering beyond its training context

- Long responses

- Using high temperature sampling

- Conflicting training data

How to Use LLMs Safely: Proper Use and Prompting Tips

Where LLMs Should Not be Used

Personal level

- Medical advice

- LLMs are not able to verify real world data accurately enough or evaluate individual risk at an appropriate level

- Can provide misleading data, misinterpret symptoms, and downplay serious situations

- If used, should be used in tandem with actual medical advice

- Financial and legal advice

- While LLMs can identify patterns, individual situations are complex and require calculated and thoughtful answers from professionals

- If it is to be used, use if for general ideas and concepts, not for specific decisions without professional advice or personal research

- Ethical or moral judgement

- LLMs, especially ChatGPT are helpful in making you feel heard and validated, but it is important to remember that it does not understand emotions

- Just because it agrees with you doesn’t mean you are objectively right; it simply makes connections based on patterns rather than understanding

Corporation level

- Regulatory compliance

- It’s important, especially in highly regulated areas like the life sciences, that human oversight is used to support proper regulatory compliance

- Legal research and citation creations

- Multiple lawyers have been fined for using LLMs that created false citations, including nonexistent cases

Prompting tips to reduce hallucinations

- Be specific, constrained, and clear in what you are asking the LLM to do

- Bad prompt: tell me about LVADs

- Better prompt: provide a brief (3 paragraph) medically accurate overview of Left Ventricular assist devices including what they are used for, how they work, and when they are typically implemented.

- Provide context

- “I am a 4th year bioengineering student trying to understand how LVADs work at the mechanical level. Can you explain this concept at an undergraduate level?”

- Ask for step by step reasoning

- “Write me MATLAB code for simulating blood flow within a patient with atherosclerosis using an LVAD. give me a step by step guide on how you wrote the code with explanations on each for each line of code. Test it yourself to make sure it works”

- Allow uncertainty, ask for confidence levels

- Bad prompt: tell me exactly how consciousness works

- Better prompt: “explain the different theories scientists propose to explain how consciousness arises in the brain and tell me if there is any uncertainty about how consciousness works.”

Tips To Stay Informed on AI

To stay informed on the current state of AI, I implement different strategies in an effort to balance efficiency and comprehensiveness.

I listen to The AI Daily Brief, a podcast providing quick, informative updates, as well as Practical AI, a podcast for technical breakdowns and implementation strategies. While podcasts like these can be insightful, I stay mindful of their ties to the AI industry, and how this may lead to a pro-AI bias.

Beyond niche media, I monitor mainstream news for the broader societal and economic implications of AI’s growing integration into everyday life. I approach these sources with caution as well, as coverage is often sensationalized in an attempt to create allegiance to or fear of AI. Consulting multiple sources minimizes the effects of these biases, which encourages me to maintain a balanced and objective outlook on AI.

In terms of integration into my own life, I test potential uses of LLM’s by comparing their responses and strategies to scientific research, manual calculations, and other LLM’s. While this can be time-intensive, it is essential for identifying my individual uses for LLM’s and other AI resources.

Ultimately, AI is a transformative technology, but it cannot be trusted blindly. Always question, verify, and think critically about the responses it gives you!

References

- 3Blue1Brown. Deep Learning Series [Video playlist]. YouTube.

- Bergmann, D. (IBM). (2025). What is Machine Learning?

- Dataiku. (2024). A Deeper Understanding of Deep Learning.

- EITCA Academy. (2023). Why is understanding the intermediate layers of a convolutional neural network important?

- IBM. (2024). What Is Deep Learning?

- IBM. (2025). What Are AI Hallucinations?

- MIT Sloan Teaching & Learning Technologies. (2023). When AI Gets It Wrong: Addressing AI Hallucinations and Bias.

- Oden Technologies. (2023). What Is Model Training?

- Towards Data Science. (2020). SGD, Mini-batch GD, and Adam Optimizer.

- Vaswani, A, et al. (2017). Attention is All You Need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

- Zhang, C, et al. (2017). Understanding deep learning requires rethinking generalization. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).